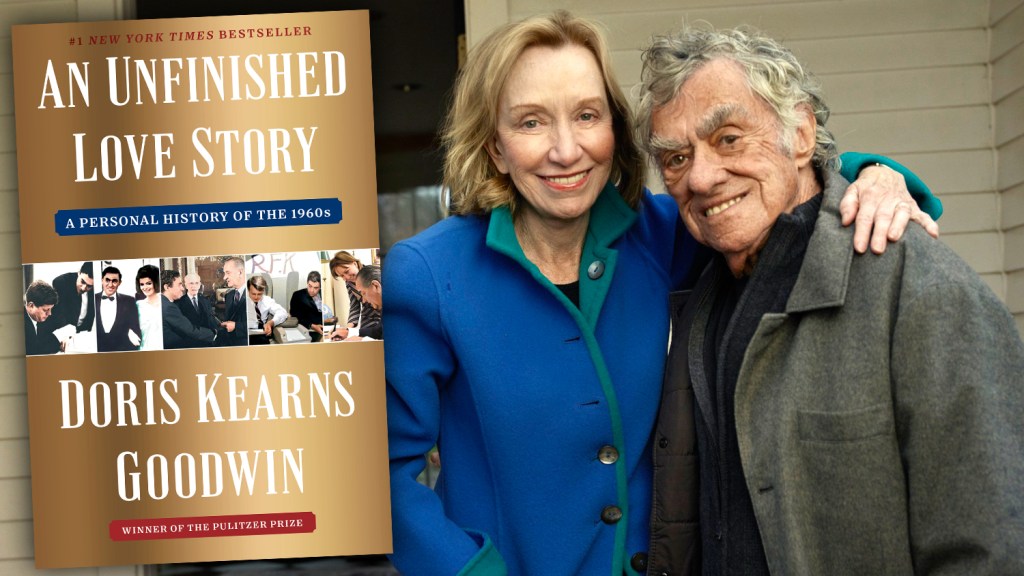

EXCLUSIVE: Playtone partners Tom Hanks and Gary Goetzman have teamed with Eon Productions’ Barbara Broccoli to acquire screen rights for An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960s. That is the book that historian Doris Kearns Goodwin wrote that debuted at #1 on The New York Times bestseller list, about the epic story of the love of her life, Richard Goodwin, peppered with his experiences as a seminal figure in the most turbulent events of the 1960s.

Kearns Goodwin and her Pastimes Productions partner Beth Laski will produce with Broccoli, Hanks and Goetzman.

“Through the eyes of friends Dick and Doris Goodwin, it is our plan to bring an intimate story of the people and events of the sweeping decade of the 1960s to the screen—a time that despite its sorrows was filled with the widespread conviction that individuals could make a difference,” Broccoli told Deadline in a statement. “Doris writing this profoundly moving book—romantic and light-hearted yet infused with deep wisdom about America—has provided this opportunity.”

CAA repped the book and Kearns Goodwin, and WME reps Pastimes. They will now look to set a writer/director to frame out what is part love story and part travelogue through the flashpoint moments of that decade. Goodwin’s trajectory came after an Army stint, a Harvard Law degree and a clerkship for a Supreme Court justice. He was tasked with heading a congressional investigation into suspicions that wildly popular TV game shows like 21 were fixed. His sleuthing ended with the bombshell confession by the erudite handsome champion Charles Van Doren that he was being fed answers in advance (Goodwin was played by Rob Morrow in the Robert Redford-directed Quiz Show). Goodwin moved to the speechwriting staff of presidential candidate John F. Kennedy, and became the youngest member of the New Frontiersmen, the group of JFK confidantes who helped him to the White House and served him there. He had a front row view and participated in everything JFK went through, from Civil Rights reforms to the Bay of Pigs and the Cold War, to the formation of the Peace Corps and the Cuban Missile Crisis. He wrote speeches that framed an era of idealism that was somewhat extinguished with JFK’s assassination. After fulfilling widow Jackie Kennedy’s wishes and securing the eternal flame that continues to burn at JFK’s gravesite at Arlington National Cemetery, Goodwin then became an advisor and speech writer of JFK’s successor Lyndon Johnson, at his side for the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that followed the globally televised brutal beatings of peaceful demonstrators at the foot of the Edmund Pettis Bridge in Selma, Alabama. Goodwin resigned his White House post because he disagreed with the escalating Vietnam War. He later became an architect of the presidential campaign of JFK’s brother Robert Kennedy. His assassination, piled on top of the murder of JFK and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr and the raging war, prompted Goodwin to exit politics. He become a writer, although he did return to help Al Gore write his concession speech after the Supreme Court controversial ruling in Bush V. Gore.

Before becoming one of America’s foremost historians, a Pulitzer Prize winner and writer of seminal books on Abraham Lincoln (a basis for the Steven Spielberg film), Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Teddy Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson, Kearns Goodwin became a White House Fellow under LBJ. She survived even after a New Republic magazine article written before she got the job was published with the headline How To Dump Lyndon Johnson. LBJ vowed to win her over and she wound up helping the president write his memoirs. She met Goodwin while at Harvard, they fell in love and married in 1975. Goodwin brought a long tail wherever they went: 300 boxes of papers he could not bear to look at because of the sadness of how the ‘60s ended.

At age 80, Goodwin was finally ready, and Kearns Goodwin and her husband spent years growing closer as they rifled through boxes filled with mementos that told the story of the turbulent ‘60s. Goodwin died from cancer in 2018, and Kearns Goodwin took her time but finished a book that connects their love story and personal history — a good natured rivalry over who was the more effective leader, his JFK or her LBJ – to create a unique intimate handle for a look into pivotal moments in American history.

I spoke with Kearns Goodwin on her collaboration with her remarkable late husband, and the contrast between the presidents she wrote about, and this moment of turbulence where Donald Trump hit the ground running with controversial moves in areas from immigration to press freedoms. She is so engaging, I thought Deadline readers might enjoy the conversation as much as I did when I spoke with her and Laski, my former colleague at Daily Variety who is her Pastimes partner.

DEADLINE: Your husband starts his political rise in the late ‘50s, tasked with unraveling the game show scandal. Then he’s at the side of JFK, LBJ, RFK, writing the most famous speeches that defined the ‘60s. What a career. And all encompassed in 300 boxes.

KEARNS GOODWIN: He was like Zelig. Everywhere you want him to be in the 1960s, he just happens to pop up there. That’s why it was possible to describe the whole decade through him, with all the inspiration at the beginning and the excitement and then the sadness at the end.

DEADLINE: He was lucky to have a wife who is a historian. If I had 300 boxes sitting around, I’m afraid that eventually my wife of 39 years would have lined them up by the curb on garbage day. Where did you keep all those boxes?

KEARNS GOODWIN: Oh my God. It was such a pain in the neck, to be honest. We would be in one house and then we moved to another, and they had to go either with us, or if they wouldn’t fit in the next house because there wasn’t the right basement or attic, then they’d have to go in storage. And then we take them out of storage, and they finally came to that last house that we lived in where there was a big barn where they could be put in and then we could move them to a study little by little when we finally decided to go through them. I had been able to look in them a little bit earlier on, and I knew there was extraordinary stuff in them. It was so frustrating for me as an historian that he just was so sad at the way the decade had ended, that he just kept wanting to look forward and just didn’t want to go through them. And finally then, as you know from the beginning of the book…

DEADLINE: He was ready to confront the past…

KEARNS GOODWIN: Finally, when he turns 80, he decides it’s time. He’s singing as he comes down the stairs. He always came down the stairs with some sort of something going on. I would have three hours of solitude until he came floating down each morning. I was so happy when he finally decided to do this.

DEADLINE: As a historian who had to scratch for research on presidents from Lincoln to FDR and Teddy Roosevelt, what was it like, cracking these boxes and coming across a note from Jackie Kennedy, or drafts of famous speeches from presidents who’ve come and gone?

KEARNS GOODWIN: Certainly, there were moments. Like when I was actually holding the blue telegram that Martin Luther King sent after the Howard University speech, saying it was the most profound speech ever given by a president. I’m actually holding it. And the difference was…I’ve spent my life going through presidential archives and trying to bring back life the presidents that no longer were alive. I would often talk to them, but they would never answer me. There was one time, I remember when my kids were little and I was writing Franklin and Eleanor, and they heard me in my room saying to Eleanor, just forget that affair that he had so many years ago. Your great partners in telling him to be kind to her. And they say, what’s going on in there? But now I have this guy in front of me. I can talk to him, I can ask him questions, I can show him stuff. It was so different from all the experiences I had before. He could also argue with me in a way that the other guys couldn’t.

DEADLINE: He held JFK in as high esteem as you did LBJ. How did you square who made the most important reforms in the fight against racial segregation and Civil Rights and the other initiatives that President Kennedy was unable to finish?

KEARNS GOODWIN: It had been not a true source of anger as much as a real irritant in our relationship because I was so loyal to LBJ and he was so loyal to the Kennedys. I would argue that Kennedy would never have gotten these bills through, and maybe the Vietnam War would have ended earlier. He would counter in return. What we came to feel, as I went through the early years of the Kennedy Papers, I began to remember emotionally not just as a historian, the inspiration of those early years. And the excitement of being on that plane in 1960 and the early days of the Peace Corps at the University of Michigan. And the debate with Nixon. And I began to feel even more [of JFK’s] inspirational capacity.

And then the most important thing that happened in going through the boxes was that he began to remember what it was like in those days with LBJ, before the Vietnam War. And the great things that happened with the Great Society speech that he was involved with, with the passage of the Civil Rights Act, with Selma and the Voting Rights Act.

DEADLINE: It lifted his sadness?

KEARNS GOODWIN: It changed. There was a sadness that was in him, really throughout his life with me. At any rate, from the time I knew him, because of the way that the decade had ended with the Vietnam War still there, and Bobby being killed and Martin Luther King, but also with his feeling that what he had done with Johnson had been eclipsed by the war and what happened to the country. But as he went through these boxes, he began to remember…there’s one night when we’d just gone through Selma and the Voting Rights Act, and he goes upstairs and he says he couldn’t sleep all night. [He tells me], ‘Oh my God, I’m feeling affection for the old guy again [LBJ]’. So that he felt a sense that what happened in the country had endured. That was in the 50th anniversaries of Medicare and Medicaid, and AIDS education and NPR and PBS and voting rights. Civil rights came through and he realized that it was still there and it made him feel a sense of fulfillment. I’ve been thinking about this in the last couple days, knowing I was going to talk to you, that in a certain sense, I fell in love with him three times. The first time was when I met him when I was 29 and he was 42 and he plopped himself down in my office. And we started talking when I was a young professor at Harvard. And we talked all afternoon, went to dinner, continued to talk, and then I went home that night and I told two friends of mine, I’ve met the man I want to marry. I knew that then.

But then I always wondered all the time…I was young when we were first married, I would say, what were you like when you were my age, when you were in your twenties? And he would say, how would I know? I was too busy being me to think about what I was like. But when I found those letters, I saw a person who greeted every day with a cheerful smile on his face, with a sense of exuberance and just pure happiness. There was this melancholy in the man that I knew, and that was not that person that I read in those letters. And that’s when I came down one morning and just said to him, I’m totally spent with you. Yes, I would’ve fallen in love with you when you were in your twenties. And then he said, and it made me sad, I’m so glad you like him so much. I rather envy him. I couldn’t understand that. I’d say, but it is you. And he said, no, it’s not. And it’s not just because I’m much older now, but I’ve lost something along the way.

And then I’d like to think I fell in love with him the third time when we went through the boxes and especially when he got the cancer. And he handled it with such grace. He had been the kind of person when he had a cold that it was a major drama, chicken noodle soup had to come, in droves. But now, he handled the operation and the radiation and everything he had to go through, because he kept feeling a sense of purpose every day by going through the boxes. We somehow believed that he would live as long as the boxes were still there to open. And so there was a sense then that that person was a different person than the one I first met when I was young. Everybody who knew him knew that something happened. Beth knew him during this time. There was something about going through this — this is why it was so emotional to me — that gave him a sense of serenity and restored that sense of the future, that still good things could happen, that it wasn’t all gone, that idealism could return.

DEADLINE: Reading up on you, I discovered that you joined LBJ’s administration, and then he discovers that you’ve written a story about how you get rid of him. Instead of getting rid of you, he says, I’m going to change your mind. He does, and later you launch your literary career writing his memoirs with him. Could that happen in this extremely polarized moment in politics, when Donald Trump started his second turn with a flurry of controversial dictates?

KEARNS GOODWIN: Now that I look back on it too, it is one of those things that’s a great story later when you’re older. But at the time, it was pretty difficult. I had worked on this article before I got the White House Fellowship. I had no idea whether it would be published or not, when I went to the White House Fellows. And then he dances with me. [LBJ] says he wants me to work directly for him. And then a couple days later, it suddenly appears with that title of theirs, how to remove Lyndon Johnson in 1968. And there were a couple of days there where it wasn’t clear what would happen. I thought he would clearly, because he had a tendency to do these things, that he would not let me stay in the program, or even worse it would destroy the program. But instead, when he finally let the word out, bring her down here for a year, and if I can’t win her over, no one can. But I only found that out afterwards when I was working on this project. I was able to find some of those white diaries that are kept where they tell you everything the President does from day to day.

President Johnson and Doris Kearns in the Oval Office

Yoichi Okamoto / Colorization by Bryan Eaton / courtesy of LBJ Library

And I found that he actually had an FBI report made on me and that he was talking to Richard Russell one night, what are we going to do about Doris Kearns? And then finally, when it was announced that he was going to keep me, there were articles ‘Swinging Blonde Wins Job Despite Being Critic.’ And luckily I’d forgotten all of that stuff. So it really was extraordinary on his part. And it turned out to be, I’d like to think, a good thing for him because I felt such enormous empathy for him. It was a great experience, especially to go to the ranch and go to Austin to help him on his memoirs. I mean, I would not have been a presidential historian if it hadn’t been for that. My field was Supreme Court history when I was at Harvard. But then that first book led to my wanting to study other presidents.

And somehow 50 years later, I’ve spent my life studying presidents who are no longer alive, dead presidents. And I like to think that I would never change it for anything. It’s just been so wonderful to catapult yourself back to different times. And the latest being the 1960s. Each time that I’ve chosen has been a time when democracy was in peril, whether it was the Civil War, the turn of the 20th century with the Industrial Revolution, the Great Depression, or World War II. Those are my times. I chose them as challenging times, and it always made me feel good to know that we got through those difficult times and actually emerged greater. So the last one of those times was the 1960s. So at the end of these 50 years of studying these people, and the only fear I have is in the afterlife, there’ll be a panel of all the presidents that I’ve ever studied, and everyone will tell me everything I missed.

And there’ll be Lyndon Johnson saying, how come that book on the Kennedys or the Roosevelts was twice as long as the book you wrote about me? But he turned out to become the most interesting political figure I think I’ve ever met. and I realized the older I’ve gotten, what a privilege it was to have spent so many hours with him. So that’s part of this story too. When I get into it in the beginning, Dick’s in the middle of it all, but then he leaves Johnson and I come in, and so then my story tells part of it. So it is interwoven in this whole book and hopefully in the movie.

DEADLINE: It is clear from speaking to you and reading this book that you feel America is resilient in overcoming all the crises that faced the presidents you wrote books about. Still feel that way, with where America is headed? On a notion, President Trump announces at a press conference his plan to take over Gaza, which is one of the most volatile places on the planes. Doris, are we going to be okay?

KEARNS GOODWIN: The question you’re asking is really what so many people ask me, sometimes even in airports or on the streets. Are we going to be okay?

BETH LASKI: Everywhere we go, people stop Doris, and with tears in their eyes and they are like, are we going to be okay? And they hug her, they cry. I mean, it’s been really dramatic.

DEADLINE: What do you tell them?

KEARNS GOODWIN: It is hard. It would be foolish to deny that this is a very difficult time that sometimes feels unprecedented. But this is where history can come in. Just think of what it was like when Lincoln came in. Seven states seceded from the Union over a war that was going to kill 600,000. And yet it ends with the union restored and emancipation secured. At the turn of the 20th century, there were anarchist bombings in the streets. There was an industrial revolution that’s shaking up the economy, not unlike the globalization and the tech revolution. There was a big gap in the rich and the poor. It was a very tumultuous time. And yet Teddy Roosevelt was able in the progressive movement to do rational reforms about the exploitation of workers.

And then when FDR comes in, this is what I have to tell people…when FDR comes in, they tell him, if you do well, you’ll be a great president. If not, you’ll be the worst. He said, ‘No, I’ll be the last.’ In the early days of World War II, when Germany swept through Europe, the entire Western civilization was at risk, and somehow the allies won that war. So it does give you perspective to look at history, and it’s one of the things that makes me so sad today, that history is being diminished. We need to look at it in order to not feel like there’s nothing we can do now, because the people living through all those earlier times, they didn’t know how it would end. Just like we don’t know. They lived with the same anxiety we feel, and somehow we came through that. So we’ve got to take some strength. We have to believe, because we’ve got to act to make it better.

DEADLINE: Your book on Lincoln explored his insistence on stocking his cabinet with political adversaries. I wasn’t a fan of Mike Pence’s politics, but the Vice President stood up for the Constitution when Trump pushed him to invalidate Joe Biden’s election win. You wonder if those people have been removed in favor of sycophants. Look at Trump’s lawsuit with CBS’s 60 Minutes over the use of different Kamala Harris soundbites. Trump has Shari Redstone over a barrel as she tries to see through the sale of Paramount Global to Skydance, and it seems he is trying to leverage $20 billion out of a lawsuit that ordinarily likely would not pass muster on First Amendment grounds. This would be a coffin nail for investigative TV journalism, if that was the price to pave way for the Paramount Global deal. From a historical perspective, how alarming is this?

KEARNS GOODWIN: What history shows us is the press is critical during every one of these times. At the turn of the 20th Century, it was the press that did all the investigations into the monopolies in food and drug problems, into corruption in the government. They were the muckrakers [exposing] business and its relationship with government. They were critical. During Roosevelt’s time, he had two press conferences a week and had relationships with the press that were extraordinary. So did JFK. The problems come when you consider the press a problem. At the beginning of Johnson’s regime, he was so open to the press, and then when the war came that closed down, and that produces a problem. I think the free press is essential. And so is having people around you who can argue with you and question your assumptions.

One of the last things that Dick wrote was just a piece that talked about the fact that maybe we shouldn’t just be looking for leaders. We’ve got to look to ourselves right now, look to the citizens. Maybe they’re going to be the only guardrails, the most important guardrails left. And that’s the argument when Lincoln was called a liberator. He said, don’t call me that. It was the anti-slavery movement and the Union soldiers that did it. The progressive movement was there before Teddy Roosevelt. The Union movement was there in the ‘30s. The Civil Rights movement was certainly there before Lyndon Johnson, and the sixties also had the women’s movement and the gay rights movement. I think that the great idealism of the sixties is something that’s so important for citizens to still feel today, that it is in their hands. I remember that first time when I was at the March on Washington in ‘63, when I was 20 years old. It was that first time I ever felt something larger than myself that I was belonging to.

And it changed me. I mean, I was carrying a sign calling for Jews and Catholics and Protestants to unite for Civil Rights, and felt that great sense of holding hands when we sang We Shall Overcome. We felt that, somehow, a better America was being born, and that I could be renewed and I could be part of it. I went back and changed my direction from taking a Fulbright and going to Europe, to staying in America. And I’d like to believe that that’s the importance of looking at the sixties again. Because it was a time of difficulty when you remember at the assassinations, the riots and the streets, the violence on the campuses, the war in Vietnam. And yet at the same time, it was a time of great movements that changed the face of the country from civil rights to women’s movement, to the gay rights movement, and citizens really feeling a sense that they could make a difference. And if we don’t feel that now somehow…I don’t see how it’s all going to happen yet. I can’t quite feel it, but in the end, if citizens have made a difference before, then that has to be what we are going to. That’s what Dick wrote in that piece, that, and he ended it by saying, America is not as fragile as it appears.

DEADLINE: So you work with your husband for years on this book, and then he does not outlive the project. How long did you put it down, and tell me about the burden and obligation of picking it back up and finishing.

KEARNS GOODWIN: It was really hard and it took a couple years. I had to make the decision of whether I could stay in this house that I loved, that we had really built into a house of books together. It was just too sad for me to go through the rooms with his not being there. I mentioned that when my mother died when I was 15, my father moved so quickly out of our house, and I couldn’t understand it. I was so sad. It was the only house I’d ever known, and when we went to an apartment, I was afraid I’d forget my mother. She was so much a part of the house. I felt the same thing. I worried, will I forget him if I’m not here? Will it be too sad to stay? What am I going to do with all these books?

DEADLINE: What did you do?

KEARNS GOODWIN: Luckily, the Concord Library came to me and created a room for the books called the Goodwin Forum Room. So 7,500 of the books went to the Concord Library, and there’s this room now there that helped to buoy my spirits, knowing that was happening. They have a plaque on the wall that replicates part of the We Shall Overcome speech that Dick worked on after Selma, [an important reminder] every now and then when history and fate meet a certain time in a certain place. High school kids go there in the afternoons. There are lectures, and events there almost every other night. That gave me a sense of, he’s still here. And then I moved into the city and then it was Covid. I’m a pretty optimistic person and have been a pretty resilient person, but that was really hard. When all those things hit at the same time, I think it was the most depressed I’d ever been.

DEADLINE: That sounds terrible…

KEARNS GOODWIN: And finally decided that maybe it was time. But it was slow. I had brought with me the couch and the table and the rug that I used to use in the other [house]. I couldn’t bring a lot of the furniture from my big old house here either, because it was all this old 19th century furniture. I just sat down there and just decided, well, let me try it. And then what’s happened, I think, is that rather than making me sad, it just brought him back to life for me because I’m going through all of it again. And then being on the book tour now, talking about him all the time, I kept thinking, oh, he’d be very happy to know he is right here. So I think it really has, I think it’s helped. I also think he would be thrilled.

DEADLINE: And now a movie keeps him, and your love story alive. What are your final memories of him?

KEARNS GOODWIN: I think part of it was just the power of his words. I mean, words really matter, and that’s something for us to remember now. When those speeches were given, whether it was the Great Society speech for Lyndon Johnson, the speech on Civil Rights for JFK, the Selma speech, or Bobby Kennedy’s South African speech…

DEADLINE: Speaking out against apartheid…

KEARNS GOODWIN: Those words are on Bobby’s grave. Each time a person stands for justice, he sends forth a ripple of hope, and then these ripples come together and they form a mighty current that break down the mightiest walls of oppression.

DEADLINE: His last words to you?

KEARNS GOODWIN: He took my hand and put it on his chest. And then he just said — and how anybody can say this at the last moment is crazy – but he said, “You are a wonder.” And then that was it.

Wedding photo of Richard N. Goodwin and Doris Kearns

Marc Peloquin / Colorization by Bryan Eaton / Courtesy of Doris Kearns Goodwin